Home » About the Area

About the Area

Peoples of the Upper Gila River

Earliest Settlements

Since 2014, field archaeologists led by Dr. Robert J. Hard of the University of Texas San Antonio and John R. Roney, retired BLM archaeologist, have been investigating multiple sites up and down the Gila River near Duncan. What they have established is that agriculture – specifically the growing of maize (corn) – was practiced in this region long before was previously thought.

These Early Agricultural Period discoveries in the region are important to archaeologists because they add a third "cerros de trincheras” and "riverine residential” area to just two previously documented ones in the Rio Casas Grandes region of Mexico and the Tucson basin.

Targeting landforms that seemed most likely to yield archaeological evidence, the team has introduced both undergraduate and graduate students to several summers of exhausting field work, documenting Salado culture structures from the Archaic/Early Agricultural period. Carbon samples from fire ring sites, tested in their laboratory back in San Antonio, proved to be maize and juniper dating to around 500-350 BC.

The UTSA team have also documented some later Classic Mimbres settlements, evidenced by pottery found throughout the valley.

The Simpson Hotel is wholly taken over by the UTSA when they come to work in the area. They set up labs indoors and outdoors, and fill all the bedrooms dormitory-style with students, advisors and visiting faculty. Toward the end of each visit they open the front doors to the public and talk about all that they’ve been working on.

Classic Mimbres beaver bowl found on the Gila River banks, directly across the river from what is now downtown Duncan (photo by Cecil O'Dell).

Since the late 19th century, farmers throughout the Gila Valley have run into prehistoric ruins while tilling fields or chasing game in the hills. Many of those old walls, ancient irrigation canals and other remnants of bygone civilizations have been forever lost to digging and leveling, and often those that are intact are guarded as family secrets. Some local farmers and others – Wilbur and Dean Lunt and Cecil O’Dell in particular – have been generous in sharing with the archaeologists what they know, including stories those sites left only in their memories.

One local fable describes an accidental discovery in the 1920s of a burial site near what is now Virden, New Mexico, just over the border from Duncan in the Gila River’s lush floodplain. The collection of ruined clay walls appeared to have been abandoned suddenly, with bowls and other implements left behind. In one of the structures, two farmers found the mummy of a warrior seated on the floor against the wall with knees raised. Laid out straight, the discoverers claimed, the man would have stood nearly seven feet tall.

The Apache

The Apache are believed to have migrated from what is now northwestern Canada in the 9th century, settling in the desert regions of the present-day southwestern US and Northwestern Mexico. They share Athabascan language group roots with the Navajo and have three distinct dialect groups of their own. Of these, the Western Apache or Coyotero settled throughout what is now eastern Arizona. The name "Apache” was bestowed on them by the Pueblo Indians –it was the Pueblo word for "enemy.”

In peaceful times, the Apache lived in extended families bound by matrilineal ties. Always outstanding hunters, they also practiced agriculture and the women became masters of basket-weaving. When, in the 17th and 18th centuries, incursions by the Spanish weighed heavily on tribes to the east and west of them, the Western Apache remained comparatively protected by the rugged topography of their tribal lands. But in the mid-1850s, gold miners and other explorers and settlers invaded the Coyotero clan’s ranges, supported by the U.S. Army. Some 40 years of unremitting, harsh warfare ensued, in which time the Apache honed their legendary status as warriors but ultimately went down to defeat and were consigned to reservations, the greater part of their lands taken from them forever.

Duncan figured significantly in the tragic and bloody end of the Apache reign over the Southwest’s lower plains and mountains. Much of this local history was painstakingly preserved by the family of Jennie Parks Ringgold, daughter of pioneers from Texas who helped settle the Duncan Valley in the late 19th century. Her memoirs, collected under the title Frontier Days in the Southwest, have been kept in print by her descendants. The book is sold at the Duncan Library and is worth every penny of its $20 price (the profits support the library). See an excerpt further down on this page.

The small highways of southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico are marked by stone pillars bearing the tales of the last stands of the Apache against an enemy they would never defeat. One of the greatest of those warriors, the legendary Geronimo, is said to have been born somewhere along the Upper Gila River. Some local historians believe it was in a cave at where the San Francisco River and Eagle Creek meet the Gila, not far downriver from Duncan.

Mexican Heritage

The upper Gila River Valley in Arizona and southwestern New Mexico were ceded to the United States by Mexico in 1848, following the U.S.-Mexico War. There are remnants of early Mexican settlements around the area.

The Old San Antonio Cemetery

Mama's Santos

Mama's Santos: An Arizona Life, by Carmen Duarte, is a detailed chronicle of a family from northern Mexico who settled in the Duncan area early in the 20th century. Ms. Duarte worked for some years as a staff writer at the Tucson-based Arizona Star, which published this story of her family as a multi-part series. It is now available on Amazon as an e-book.

There has been considerable attention paid in recent years to the roles of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in the great copper mines of Greenlee County. Los Mineros, a documentary film produced in 1991 by Hector Galán and aired on PBS’s The American Experience, probes the struggle of Mexicans laboring in the copper mines of Morenci in the early 20th century to end a discriminatory dual pay system. Read the Los Angeles Times' review.

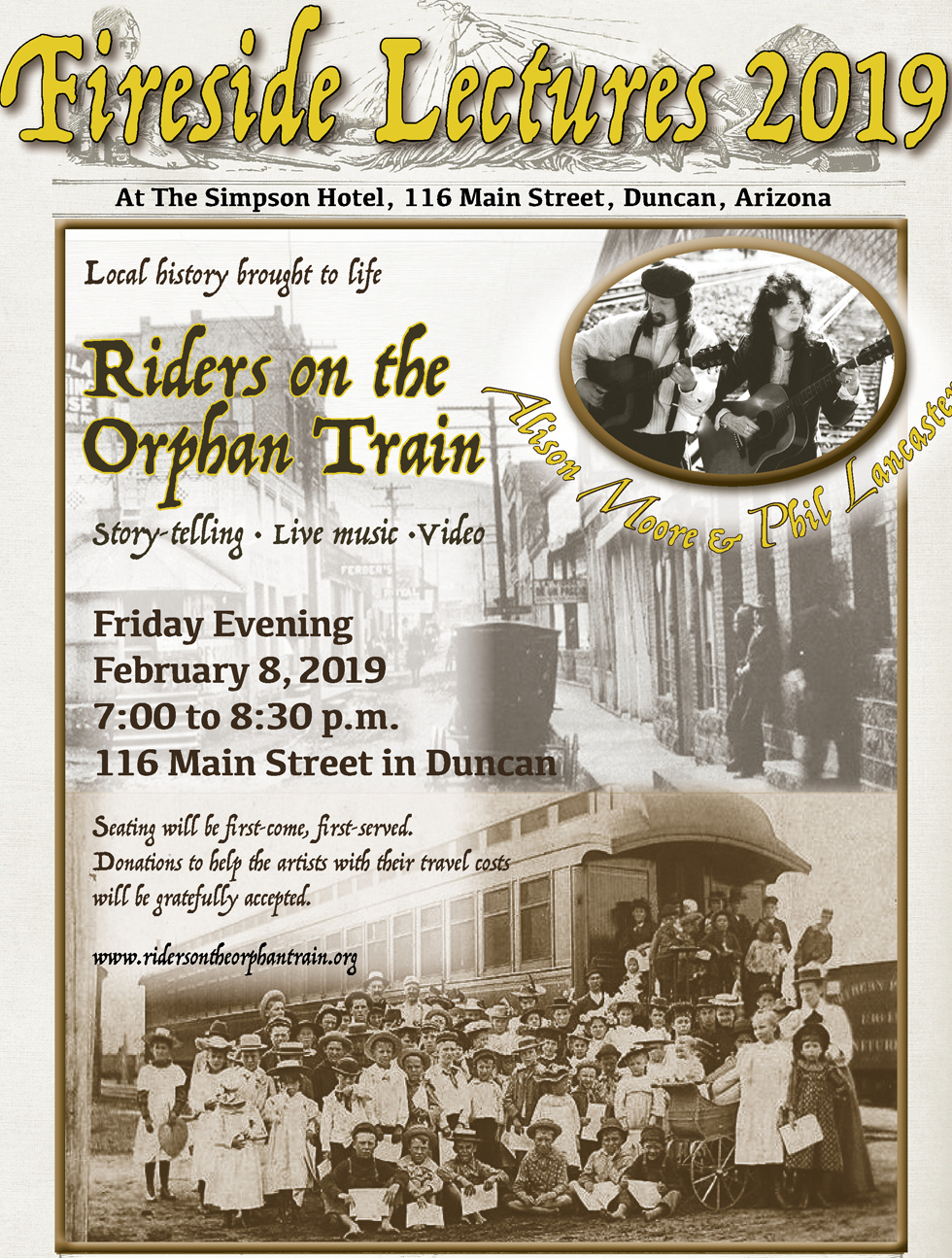

The Great Orphan Abduction

Also set in Morenci and neighboring Clifton, the "great orphan abduction” of 1904 still ranks as one of the most notorious chapters in Arizona’s history. The case went all the way to the Arizona Supreme Court and fastened the attention of a disapproving nation on the anti-Mexican mob rule of white residents in the segregated mining community. The Simpson Hotel itself features in the ongoing legacy of this d isturbing tale. Ask us about it when you visit.

In 2018 we welcomed Riders on the Orphan Train, a presentation of history, film and music on this tragic story by Alison Moore and Phil Lancaster. Alison has also published a book, Riders on the Orphan Train.

The orphans' story has captivated many other writers over the last century, notably the historian Karen Wells, whose scholarly book, The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction, was published in 2004 by Harvard University Press. Borrow our hotel library copy while you stay with us.

Latter Day Saints and Arkansans, Italians and Romanians and Chinese

The lure of the world’s greatest copper mines drew workers and families from lands much further away than the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts of Northern Mexico. In the last century the Upper Gila region drew people of Chinese, Mediterranean and Southern European descent to work the many copper, gold and silver mines. And like much of the Southwest, a slow but steady trickle of Arkansans and Oklahomans in particular has flavored the region’s cultural mix.

Among all of these, only the Chinese have left without a trace. One well-known elder in the community remembers visiting Chinese-owned shops in all the settlements around Duncan. Except for the ailanthus trees that grow everywhere like weeds, and an occasional find of Chinese pottery sherds, that chapter is closed and nearly forgotten.

If you look along the tree line on the north bank of the Gila River in Duncan, you’ll see the distinctive slim spire of the Latter Day Saints house of worship. LDS culture has long been an anchor of the town’s prosperity and stability. How some of the area’s first Latter Day Saints came to this valley by way of Chihuahua, Mexico, where they had earlier fled to practice their religion and family life undisturbed by authorities, was a direct result of the Mexican revolution. One of those stories is told in Carmen Duarte’s Mama's Santos: An Arizona Life, now an e-book on Amazon. An equally good read is Heaton Lunt, Of Colonia Pacheco: Bronc Buster, Scout, Bishop, by Marian R. Lunt, available to borrow at the Duncan Public Library or to buy on Amazon. We have copies of both at the hotel.

The Coronado Expedition

No survey of the Upper Gila Valley's history would be complete without reference to the adventures of gold-obsessed Spaniards searching for the City of Cíbola. In 1540 Francisco Vásquez de Coronado and his party made their historic trek through what is now Southeastern Arizona and Southwestern New Mexico. The "Coronado Trail” highway from the San Francisco River into the White Mountains is the monument to that history most often sought out by tourists to the region. Clifton and Morenci, Duncan's closest neighboring towns, are on the official Coronado Trail.

But have historians missed something? Read on.

The following passage is extracted from an essay by New Mexico State Engineer Buck Wells, who has been studying the old Indian trails of New Mexico and Arizona for many years. Long fascinated as well by the Coronado expedition, Buck, in collaboration with other historians and history buffs, has constructed a well-reasoned argument that the Spanish explorer might have passed through what is now Duncan.

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado (c. 1510-September 23, 1554) was a Spanish Conquistador who, between 1540 and 1542, visited New Mexico and other parts of what is now the Southwestern United States. Born in Salamanca, Spain, he was governor of Nuevo Galicia, a province of New Spain comprising the contemporary Mexican states of Jalisco, Sinaloa and Nayarit. In 1539, he dispatched Friar Marcos de Niza and a survivor of the Narváez expedition, named Estevanico, on an expedition north toward New Mexico. When Marcos de Niza returned, he told about a golden city called Cíbola, where Estevanico had been killed by its Zuni citizens. Though he did not claim to have entered the city of Cíbola, Marcos reported that it stood on a high hill, that it was made of gold, and that he could see the Pacific Ocean off to the west.

Based on this report, an expedition funded by both Coronado and his good friend Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza was mounted. Setting out in 1540 with 335 Spaniards, about 1,300 natives, four Franciscan monks and several slaves, both native and African, Coronado followed the Sonoran coast, keeping the Sea of Cortez to his left. He rested his party at the northernmost Spanish settlement on that route, San Miguel de Culiacán, before commencing the long trek inland. Scouts were sent out ahead to see if the land along the route would be able to support a large body of soldiers and animals. They returned to say that it would not, so Coronado divided his expedition into small groups and staggered their departures so that grazing lands and water holes along the trail would recover. He established camps and garrisoned soldiers to keep the supply route open. When the scouting and planning were done, Coronado led the first group of soldiers up the trail – horsemen and foot soldiers who could travel quickly. The rest of the expedition set out at intervals behind them.

After leaving the last Spanish settlement, they traveled northward through Sonora and crossed the Gila River, the Mogollon Rim and the Little Colorado River, then following the Zuni River drainage into Cíbola, in the western part of present-day New Mexico. There they met a crushing disappointment. Cíbola was nothing like the great golden city that Marcos had described. Instead it was a complex of simple pueblos constructed by the Zuni Indians. The soldiers considered killing Marcos for his mendacious imagination, but Coronado intervened and sent him back to Mexico in disgrace.

The Route

After a four-day crossing of despoblado or uninhabited area, Coronado entered what is now the United States in Southern Arizona. Most scholars believe that he entered along the San Pedro River. Recent research suggests that he turned south of Benson and proceeded through the Sulphur Spring Valley toward Safford.

Along the San Pedro, lined with thorny trees much as it is today, Coronado and his party encountered poor Indians who presented them with wild plant foods, as was the local custom. Seymour (2008) has suggested that these natives were probably the resident migrant groups later referred to as the Jano and Jocome, who subsisted on wild plants and animals. It seems that Coronado did not encounter the Sobaipuri as Bolton and many historians have assumed, because he turned before reaching their southernmost settlement. Marcos de Niza, who had traveled that way 11 months earlier, likely did encounter the Sobaipuri.

So which way did Coronado travel north onto the Mogollon Rim? Could the old Indian trails leading up Apache Creek and over the escarpment to Mule Creek be it? Or is a grassy plateau overlooking Duncan, where schoolboys in the 1950’s say they found a Spanish helmet and a sabre, from which it is an easy climb to that same escarpment, also a possibility?

The Apache Wars

No one knows for certain where the Apache originated, and some historians believe that they were driven out of Northern Mexico by Spanish settlers. Thus they had made the region that is now Arizona and New Mexico their home not long before that too was taken from them. On May 17, 1885, a group of Apache Indians fled the San Carlos Reservation, hoping to regain the unrestricted life they had led before being confined by the U.S. government to reservations. Led by the shaman-warrior Geronimo and other fierce and courageous men, the group consisted of 35 men, eight boys, and 101 women and children. As noted by historian James Hurst in his essay "Geronimo's surrender — Skeleton Canyon, 1886,” this group "…would occupy the attention of five thousand troops, five hundred Indian auxiliaries, and an unknown number of civilians. In an area roughly the size of Illinois and comprising some of the roughest desert and mountain terrain in North America, they maintained themselves for sixteen months. In that time they killed seventy-five citizens of the United States, twelve White Mountain Apaches, two commissioned officers and eight soldiers of the regular Army, and an unknown number of Mexicans. The Apaches lost six men, two boys, two women and one child.”

Duncan figured significantly in the tragic and bloody end of the Apache's reign over the Southwest's lower plains and mountains. A great deal of this history was painstakingly preserved by Jennie Parks Ringgold, daughter of pioneers from Texas who helped settle the Duncan Valley in the late 19th century. Her memoirs, collected under the title Frontier Days in the Southwest, have been kept in print by her descendants. The book is sold at the Duncan Library (the profits support the library).

The Carlisle Mine

The ruins of the mine at Carlisle, in the Steeple Rock District of Grant County, New Mexico, are just a few miles northeast of Duncan on a well-maintained dirt road. Local historian Richard Billingsley created this merged image with an old photo of the mining settlement and a shot of the landscape as it looks today (we added the photo of young Herbert Hoover with other engineers and the caption). None of the buildings still stand, but the foundations and a tremendous amount of scrap are still there to pick through. What appears to be a jail cell, a cave carved out of a mountain, the opening secured with iron bars, is said to be just that.

Old photo of Carlisle Mine buildings superimposed on a contemporary photo, by Richard Billingsley

Starting in 1893, the gold, silver and copper being pulled from the Carlisle mine attracted thousands of workers and put in place all the businesses needed to sustain a lively mining town. In 1898, a young Herbert Hoover, three years out of Stanford, arrived at Carlisle as assistant superintendent of the Steeple Rock District Mines. He was put up in the home of Superintendent P.H. McDermott, who was also the hard-drinking little settlement's deputy sheriff. Local legend has it that Hoover himself spent a night in that cave jail for drunken and disorderly conduct. He is said to have protested, "The Mexicans and Indians made me do it.”

At the time Hoover arrived, the mine was already in decline and a few years later it shut down until 1932, when new mining and milling techniques allowed for another 15 years of productivity. But since then Carlisle has declined from ghost town to ruin. It is a popular spot for rockhounds today.

Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor

Although she was born in El Paso, Justice O'Connor – born Sandra Day – spent much of her childhood near Duncan on the Day family's Lazy B Ranch, which straddles the Arizona-New Mexico border. Her book Lazy B: Growing Up on a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest is in our hotel library. The Round Mountain rockhounding area south of Duncan is accessed through the Lazy B Ranch across the border in New Mexico. Different owners now run cattle on the ranch and its huge federal land grazing lease. It’s a beautiful drive over well-maintained dirt roads, and the cowboys there won’t bother you at all as long as you don’t bother them.

Hal Empie

No discussion of the Duncan area is complete without a deep bow to Hal Empie, Duncan’s pharmacist in the mid-20th century and a renowned Western painter and cartoonist. Empie’s influence still permeates the town, as many older residents have vivid memories of his warm welcomes in the drug store, his generosity with local children, his ability to paint in his drug store art studio in between waiting on customers, and his propensity for theatrical antics, many of which are contained in a DVD of Empie home movies sold at the Duncan Library as a fundraiser for the library (courtesy of the Empie family).

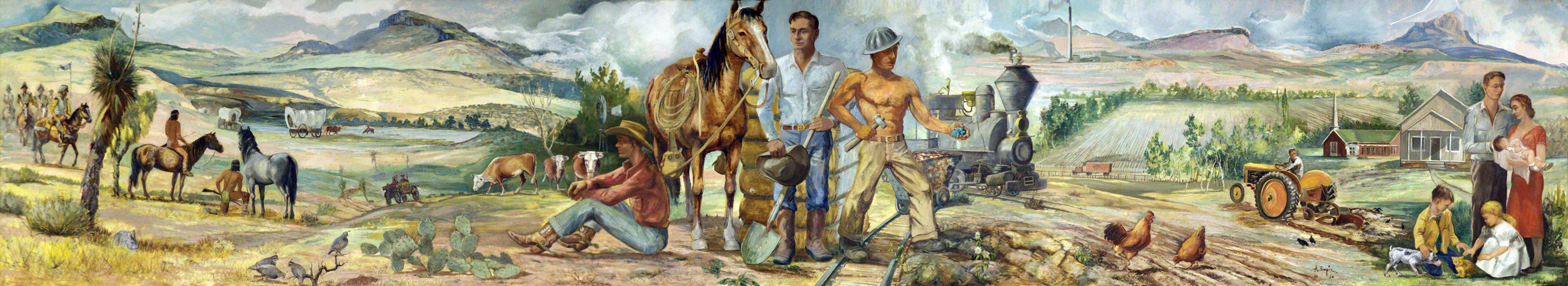

Scroll for a panorama

Empie’s 6’ x 30’ historical mural "Greenlee” hangs in the Duncan High School cafeteria, which is open to the public during school hours only – roughly 8-3, Monday through Thursday, August through early June. It is possible sometimes to arrange to see the mural at other times; please ask us.

Empie’s daughter Ann Empie Groves worked for years compiling a book of Hal Empie’s cartoons, which are still collected throughout the West and beyond. The book is now available. For more information, see www.halempiestudio-gallery.com.